The first time I heard Lukas play, he was already better than any mortal fiddle player I had ever heard. The music had him enraptured, so I could creep out of the cold depths of my stream to listen. He threw himself into the song, his lithe body swaying to and fro with its rhythm, but still stomping out the time for the non-existent dancers. He was beautiful.

The first time I heard Lukas play, he was already better than any mortal fiddle player I had ever heard. The music had him enraptured, so I could creep out of the cold depths of my stream to listen. He threw himself into the song, his lithe body swaying to and fro with its rhythm, but still stomping out the time for the non-existent dancers. He was beautiful.

When he stopped, he opened eyes the color of a clear blue midday sky, a sky I have not seen in so many years. His gaze was unfocused, and at first, he did not notice he was being watched. When he saw me, he smiled.

“Stromkarl,” he said. “Teach me to play.” He gestured to the white goat at his feet, curled up as though asleep, its head turned away from my waterfall. And it was Thor’s Day. He knew what he had done, what he planned to do.

But despite him making the appropriate sacrifice to receive the Stromkarl’s blessing—my blessing—I looked away.

“I will teach you. But you must come back next week.”

“I am here now. Teach me now.” His voice was bold and strident, lacking the fear that so many had when they came to me.

I narrowed my eyes. “Do you know what you ask of me?”

He nodded, a twinkle in his eye.

I saw it as a challenge.

I pulled my fiddle and bow out from beneath the water. “Follow my lead, then.”

Though his brow creased, he lifted his fiddle to his chin. This was not what any mortal man expects when they bring a sacrifice to the Stromkarlen. They expect instant gratification.

I began to play one of my favored songs, and he followed, as bade. As we went on, I increased the pace. He kept up for a time, but soon he grew weary, and my playing continued to quicken. With a snarling squeal, his fiddle fell silent, and he dropped his bow from swollen fingers, disappointment plain on his face.

“Come back next week,” I said again.

He came back the following Thursday, another goat in tow. He unwound long, ragged bandages, tinged pink, from his hands. As he flexed his fingers, he asked, “Is this what they mean when they tell us the Stromkarlen will make all of our fingers bleed?”

I shook my head, curls cascading down my bare shoulders. I had made myself look more like him—more human—but he did not seem to react to this change.

“Then do I follow your lead again?”

I nodded, retrieved my fiddle and bow, and began the same song we had played together the previous week.

This time, Lukas kept up, all the way to the end.

So I began another song.

This one was meant for two fiddles, playing in unison in parts, and playing intertwined melodies as the song went on. I gave him the main melody, and then I diverged from it. But he followed my divergence. I returned to the original melody, and he did as well.

There is no signal that is shared between two musicians who have barely played together, so I had no way of keeping him from following my lead without stopping the song.

And I could not stop the song.

But I could wait until he had fallen so deep into the song’s spell that he would not notice when I played my own melody. So we played together.

When it came time for me to play the melody I had concocted, the entrancing music had transformed Lukas into a luminous, being.

And with his perfection, I was enraptured .

My fiddle fell silent, and Lukas stopped, blinking away the spell. “Did I do something wrong?” he asked, fear creeping into his tone like tinkling bells.

“No,” I replied, but my voice was husky, a bass too quiet for him to hear. I repeated myself, and then said, “We are done for tonight. Come back next week.”

Lukas frowned, but he nodded. He stooped to pick up the bandages he had left strewn beside the stream.

“Leave them,” I whispered.

His frown deepened as he looked up at me. “Why?”

I drove my thumbnail into the palm of my hand and showed him the trickle of blood that ran down it. “For my wounds.”

He scoffed. “I thought you to be of the Stromkarlen. They do not bleed like men.”

“I am a Stromkarlen. I am called Hemming,” I said.

Lukas handed me the bandages, his previous harsh words now tempered by a shy smile . “Well met, Hemming. Tend to your wounds, for I shall return next week.”

As soon as Lukas was out of sight, I staunched the bleeding of my palm. I did not want to sully Lukas’s bandages with my foul blood. Instead, I wound them around my arms, crossed my wrists near my neck, and breathed in Lukas’s scent.

Lukas did not bring a goat the following Thor’s Day, and his posture had changed. He seemed impatient, his fiddle beneath his chin and bow poised to play, one foot tapping not a rhythm for dancing, but a hurried pace too fast for any song.

“What is wrong?” I asked. The bandages had lost his scent after one day in the water, so I had discarded them. I looked just as I had on his previous visits.

“I don’t have time for this,” he said, his voice tense like strings wound too tight. “I brought you an offering, twice now, and I still can’t play well enough.”

“You play beautifully.”

He shook his head. “It’s not enough. I need to be the best.”

“Why?”

Lukas let out a long sigh, like the music of the wind through the trees, and looked away from me as he spoke. “My parents live in constant fear of losing their farm. There is a fiddle competition in the city, next Thor’s Day. I came here to receive your blessing so I could win the competition, and so they would never again have to worry about money.”

“A noble gesture, from a devoted son,” I said. “But you show so much promise, I fear another Stromkarl has already granted you his blessing.”

“Hemming, none has. Do you want me to get another goat?” His voice took on a pleading, whining tone that grated at my ears . “I’ll bring you one straight away. Just grant me your blessing now, before it’s too late. Please.”

Tears shone in Lukas’s eyes, and I longed to embrace him, to wipe away his tears. But that was not the embrace he desired.

I nodded and moved into position behind him. Plucking the bow from his right hand and setting it on the ground, I placed my hand over his hand. Our fingers curled together. I pulled his hand across the strings in a rush of blood and pain.

He screamed.

I dove into the water so I would not have to hear my dear Lukas’s pain. It would be a melody that I could never bear to hear.

Two weeks later, I smelled the goat before I heard the music. I had not emerged from the water in that time, sulking beneath the placid mountain lake where I made my home. The aroma reminded me I had not eaten in quite some time.

I surfaced enough to see who had brought me a gift this time and was astonished to see Lukas, playing the first song we had played together.

For a moment, I considered sinking back down into the water, refusing his gift, refusing to speak to him. What more could he want from me?

Curiosity, and hunger, got the best of me.

I watched Lukas, waiting for his eyes to close, before I made my approach. But his gaze remained fixed on the water. He locked his gaze to mine, and said, “Come, Hemming. I have brought you a gift.”

I remained in the water, though I swam closer to the shore, so I could speak to him. “Why?”

“I won the contest. I thought it right to share the spoils with my teacher.” His joy rang out like church bells.

I shook my head. “You learned nothing from me. You only received my blessing.”

His fiddle screeched to a sudden stop. “No. You were right. I didn’t need your blessing to win. I was wrong to insist upon it. I came back to apologize. And to ask if you would play with me again.”

I emerged from the water, my body shaking with hunger. I could not play in this state. Picking up the goat with trembling arms, I tried to turn away from Lukas to eat, but he steadied me with a hand on my shoulder.

“I want to see you as you are. You needn’t turn away, Hemming.”

My jaw unhinged, and I consumed the goat in a single swallow.

His gaze never wavered.

“Now, may we play?” he asked. His hand remained on my shoulder, caressing my skin.

I ran my hand along his cheek, and he leaned into the touch, already moving to the music we could make together.

“Follow my lead.”

Please support the work done on Truancy Magazine via Ko-Fi!

Bio: Dawn Vogel’s academic background is in history, so it’s not surprising that much of her fiction is set in earlier times. By day, she edits reports for historians and archaeologists. In her alleged spare time, she runs a craft business, co-edits Mad Scientist Journal, and tries to find time for writing. She is a member of Broad Universe, SFWA, and Codex Writers. Her steampunk series, Brass and Glass, is being published by Razorgirl Press. She lives in Seattle with her husband, author Jeremy Zimmerman, and their herd of cats. Visit her at http://historythatneverwas.

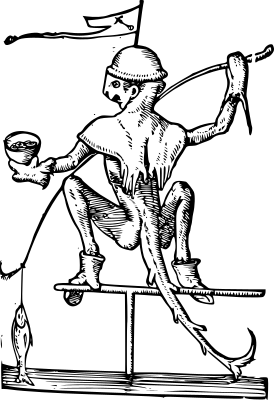

Bio: Dawn Vogel’s academic background is in history, so it’s not surprising that much of her fiction is set in earlier times. By day, she edits reports for historians and archaeologists. In her alleged spare time, she runs a craft business, co-edits Mad Scientist Journal, and tries to find time for writing. She is a member of Broad Universe, SFWA, and Codex Writers. Her steampunk series, Brass and Glass, is being published by Razorgirl Press. She lives in Seattle with her husband, author Jeremy Zimmerman, and their herd of cats. Visit her at http://historythatneverwas.This 1565 illustration from Rabelais’s “The Life of Gargantua and Pantagruel” was sourced from here.