“Stay away from Sang Kancil,” Sang Buaya would warn me. I did not care to argue with my guardians. “He is clever and tricky, and will waste no time taking advantage of your goodness.”

Through groundwater paths, through streams and trickles between hills and mountains, I stretched my being as far and wide as possible, exploring the world through its breathing earth. Where I wandered, I listened to the warbling of Tiong and Merpati, the nighttime shrieks of Keluang and Kelawar high above my head as I passed through the roots of trees.

“Ya Si Jernih!” they would cry, “and where do you go today?”

What a question! Wherever I go, of course. Who stops a river’s inexorable course? But there are times I stepped out of my element to wander inland, whispering myself into the morning mists, or the humidity between trees. I espied Sang Sawa on a tree waiting for prey.

“Good morning, Sawa,” I said to the snake. “Good hunting today?”

“Not yet, not yet,” Sawa replied. “But one must have patience, ya? One must wait. I can wait.”

“Have you seen Sang Kancil today?”

“I haven’t seen Sang Kancil for a long time, now that I think about it.”

“Oh, all right. I’ll keep looking, then.”

“You do that, Cik Sungai,” Sawa said agreeably. “When you find Kancil, mention me. I may eat mousedeer, but Kancil’s company is always very pleasant when we are not fighting.”

With that, Sawa curled up tighter on the branch and began to doze.

“You did what?” Sang Buaya roared when I told him of my day’s wanderings. “I told you to stay away from him!”

I still took care not to argue with Sang Buaya. He meant well. “At least,” I said, “I did not run into Agan Pelanduk.”

“You are trying to make me angry,” Sang Buaya growled. “Stay away from that whole family!”

It was amusing to see such a normally well-contained creature like Buaya burst out like that.

One evening, as I rolled inland with a fog, I found chevrotain footsteps, and followed them until they disappeared under a group of ferns. Nothing there but a bed of moss and Little Cacing, who lifted his blind head at my coming.

“Where is Sang Kancil?” I asked.

“Long gone, Puteri Paya. I last felt that family’s heartbeats thrumming through my skin months ago, resting while they ran from Sang Harimau.”

“And have you seen Sang Harimau lately?” It occurred to me that I myself had not seen Sang Harimau in a long time. The tigers came to my banks less and less.

“No, Puteri Paya. I last felt any of that family weeks ago, hunted by Man.”

“What a fool!” Sang Buaya cried when I reported that to him. “Harimau knows that men wreak vengeance for anything!” He was quiet for a while, and then asked, “no sign of Sang Kancil then? What about Si Babi, or Tun Tapir?”

“No sign,” I said, and we were both troubled by this.

I avoided the towns of Manusia as much as I could. In the belukar, Musang and Monyet would regale me with stories of infiltrating their houses, which were never quite as exciting as the adventures of Tupai and Tikus dodging housecats and dogs.

I grew slower, I became more tired. I stopped wandering as I did before, but one rainy day, I came across Sang Harimau catching a deer. It struggled in his grasp for a few moments, but they both turned their heads to me as I approached.

“Your time is coming, Puan Kuala,” he noted.

“All our times will come, Sang Harimau,” I said, “just as Si Rusa’s time has come at your claws.”

“It is the nature of living,” Si Rusa agreed.

“I have passed through the whole land, met all the animals, and not seen Sang Kancil once. All the forest folk come to drink at my banks at least once, but Sang Kancil either avoids me or is lost.”

“I saw him a while ago,” Rusa said. “He is very good at making himself scarce.”

“As do you, and all other creatures of the forest.”

“Bad luck this time, Puan,” Harimau said, and then added with a note of good cheer, “perhaps next time?” With that, he batted Rusa’s head once, and sank his teeth into the deer’s neck.

Rusa’s expression was one of shock at death, although I’m sure he was not entirely surprised at Sang Harimau’s actions. The light in his eyes died and his head fell to the side with a shudder.

I passed through a city of Manusia and was glad that Sang Buaya had not followed me from the forests. He would have been appalled at the high walls along the sides. There was all manner of rot in my waters now, but still, a few inhabitants seemed to think me clean enough to fish in.

I poured into the sea, and my every droplet dispersed. The saltwater weighed me down into a permeating embrace, until I was not me, but we: every stream turned brooke turned waterfall turned river rushing towards our end. Rolling, roiling waves hushed and shushed songs of sleep, deep into the underworld trenches. We stretched ourselves across the sea, and felt the sunshine cast glinting kisses off our surface. The heat beckoned to us to evaporation, to new oblivion. Rising to the skies, I stretched out across the land again, letting the wind blow me whichever way it would. From there I saw Sang Kancil cavorting with his family. He looked up at me as I clouded over him and the yam leaf he sheltered under.

“Wahai, Anak Hujan!” he called to me. “I hear you’ve been looking for me!”

“Where have you been?” I inquired. “I would have thought Sang Harimau would have caught you by now.”

“Yes. Sawa, Buaya, Harimau… and all the other animals that would love to feast on my flesh! We have an agreement, they and I. It is the nature of living.

“If Harimau were to catch me tomorrow, I would accept my fate,” Sang Kancil continued, “but Manusia catching me with his new tools and tricks! I refuse!”

Warm air mixed with the cold of my essence created a thunderclap that made all the animals, and some men, sit up.

“Hujan Ribut!” Sang Kancil cried in a way I had never heard from any of the creatures before. “Destroy and wash away the pride of men! Humble him and remind him that there is a cycle, there is no more and no less. Grief is not for him to deal out!”

He kneeled as a supplicant then, and it seemed the other animals heard him, and agreed, and they too lowered their heads.

I roared, once, twice, then rumbled across the skies, and washed down on the cities of men, trying to do as much damage as I could in answer.

I awoke in one of the high places that was still deeply forested. Ferns sprouted across all surfaces, mosses grew so thick they were webs of cushion. Sang Kancil was drinking from me, trickling sounds from his tongue. Sawa was nearby, lounging on a tree branch; his head rested on a leaf.

“Did I—?” I wondered aloud.

Sang Kancil shook his head. “You blew a few electricity fuses, but that was all.”

“Bad luck this time,” I said.

“Better luck next time!” he replied cheerfully, and jumped nimbly from Sang Harimau’s pounce. His laughter emanated from the shrubs he disappeared into.

Harimau was still hungry, so he thought to try Sawa instead. Sawa was not interested in dying that day, though, so he knocked Harimau down as hard as he could on the head.

And so it goes, encounter after encounter, life after life.

Jaymee Goh is a writer of fiction, poetry, and academese. She is currently a PhD Candidate at the University of California, Riverside. Her work has been published in Strange Horizons, Expanded Horizons, Stone Telling, and Crossed Genres. She is an editor of The Sea is Ours: Tales of Steampunk Southeast Asia (Rosarium Publishing). She tweets and Tumblrs at @jhameia.

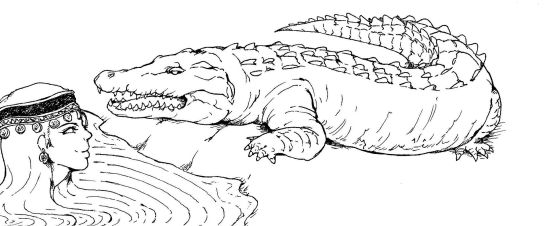

Illustration by Akira Lee. Akira is a Universiti Malaya student by day, geek and manga enthusiast by night. Drawing and writing by the moonlight. Accepting commissions at motesandshadows AT gmail.com